Early last month I visited the Powerhouse Museum on the last day before it closed indefinitely. I perused the 1001 Remarkable Objects exhibition but most of the other galleries had already been gutted. Government obfuscation means that there are conflicting reports on what kind of venue it will turn out to be when and if it reopens. My visit prompted me to look back at several contributions I have made to the written history of this once great Sydney museum.

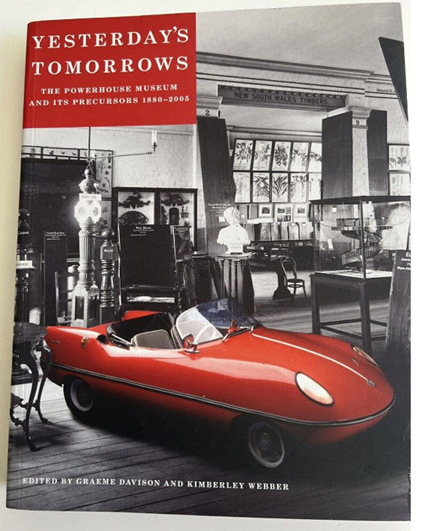

Nearly twenty years ago the Powerhouse produced a large and handsome book to celebrate its 125th anniversary. The authors of its chapters ranged from museum staff to academic historians. The diversity of their topics covered not only the sometimes colourful history of the museum, but the spread of its vast collections, representing as they do science, technology, design, decorative arts and social history.

My colleague Martha Sear and I, both of us curators at the time, wrote a chapter titled ‘Prescribing’ where we followed the museum’s intermittent efforts to encourage health and hygiene amongst the general populace. Indeed its first name was the Technological, Industrial and Sanitary Museum. Original exhibits included an arrangement of sanitary appliances, such as toilets, sinks, ventilators and pipes, for the instruction of tradesmen and householders.

From the early educational displays of human bones and papier-mâché anatomical models as well as plumbing, through the eugenically ideal Transparent Plastic Woman of the 1950s, the confused 1980s Mind and Body gallery, and on to exhibitions about contraception in the 1990s and sustainable futures in the early 2000s, Martha and I found a common philosophy underpinning the museum’s intentions in its health and hygiene displays.

We concluded that, despite changes in its name, site, and governance, and despite the evolution of international museum trends, the Powerhouse and its precursors had always assumed an admonitory role in those displays. That is, it insisted that visitors were responsible for managing their own health, and it showed them what it regarded as the means to make informed choices about how to achieve that.

But even though the purview of Yesterday’s Tomorrows was wide, I was disappointed that the book gave little attention to the viewpoint of visitors. Once our chapter had been signed off I saw the opportunity to go on and fill a research gap. Across the world few studies had been made of people’s experiences of museum visits made before the 1980s, which is when the field of visitor evaluation emerged.

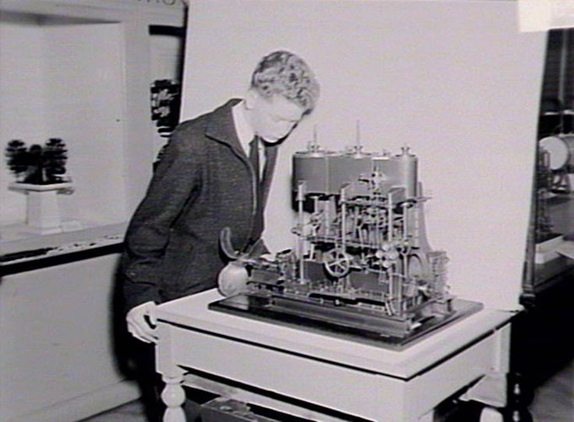

With encouragement from Bruce Hayllar at the University of Technology Sydney I conducted a series of interviews with people who remembered visiting the Technological Museum (as the Powerhouse was then known) as children or teenagers between 1935 and 1969. Over those decades the museum suffered from lack of funds and its didactic and overcrowded exhibits barely changed.

I do not have much of a following as a researcher/writer but, of all the articles and chapters I have published, my study of young people’s experiences of the Technological Museum is my most cited work. That’s probably because there are – or were – more students and researchers interested in visitor studies then there are aficionados of pavements and pavement graffiti. Nevertheless I thank Bruce Hayllar for prodding me into making this a much better article than it might otherwise have been.

By taking a phenomenological approach to the interviewees’ fragmentary long-term recollections I was able to capture an insight into the lived experience of museum visits from a young person’s perspective. I concluded that there were three themes characterizing their experiences. These were City Life, Adulthood and Independent Discovery. Linking these three themes was the fundamental experience of Growing Up. For young people of the period 1930- 1970, visits to the Technological Museum contributed to their transition from childhood to adulthood.

For a retrospective visitor study of a museum that was at the time old-fashioned by world standards, that was a pretty remarkable finding.

References:

SCORRANO, Armanda (2006) (Book review) Yesterday’s Tomorrows: the Powerhouse Museum and its precursors 1880-2005 [etc ]. Public History Review, 12, 111-113.

DAVISON, Graeme & WEBBER, Kimberley (Eds.) (2005) Yesterday’s Tomorrows: the Powerhouse Museum and its Precursors 1880-2005, Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing with UNSW Press.

HICKS, Megan & SEAR, Martha (2005) Prescribing: salutary instruction at the museum. In WEBBER, K. & DAVIDSON, G. (Eds.) (2005).

HICKS, Megan (2005) A whole new world: the young person’s experience of visiting Sydney Technological Museum. Museum & Society, 3, 66-80.