Sunday 19 April 2020

It’s over three weeks since we visited this light industrial triangle between Johnstons Creek and Pyrmont Bridge Road. There have been other excursions in between but now I’m back to find out what happens to the creek beyond the forbidding metal fence where it drops into an open canal behind Water Street. Just a few neatly kept little houses remain here, tucked between hulking factories and warehouses, and we have come on a Sunday hoping to avoid large trucks squeezing into delivery bays. I walk down a driveway between two houses in Water Street and find that it opens onto a gravelled space bounded on three sides by buildings and on the fourth by a thick jungle of banana trees, castor oil plants, convolvulus and asthma weed. With no machete available I can only peer down the steep slope for glimpses of the canal wall, recognisable by its symbiotic graffiti.

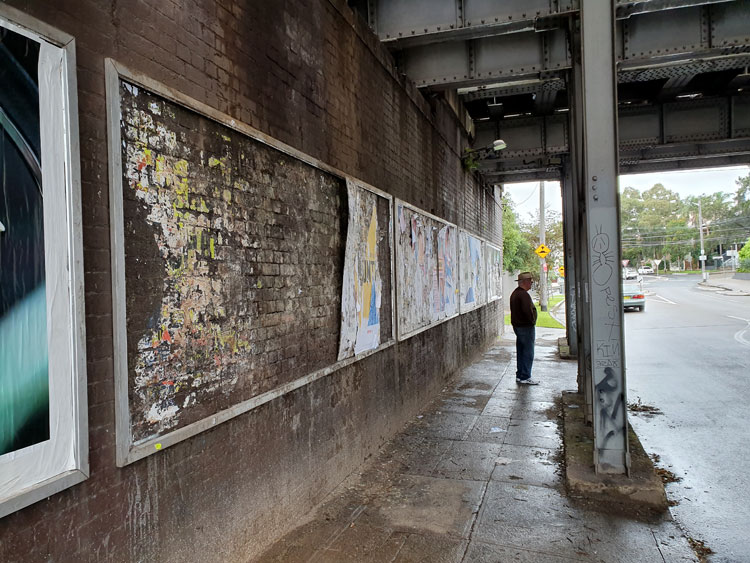

Frustrated by the banana jungle we move east to a wider industrial street that leads directly down to the canal. I have never been on Chester Street before but later I will read that there was once a household garbage tip amongst the houses on this side of Johnstons Creek. It was the source of much friction between the adjoining boroughs of Camperdown and Annandale in the late 1800s. For fifteen years countless newspaper column inches were taken up with reports of council meetings and letters to the editor on the subject of the Camperdown tip, whose ‘deadly effluvia’ made the creek filthy and ‘endangered the lives of the residents of North Annandale’. There are no houses here now and no tip. Instead there is a motor repair business with a wild piece of wall art.

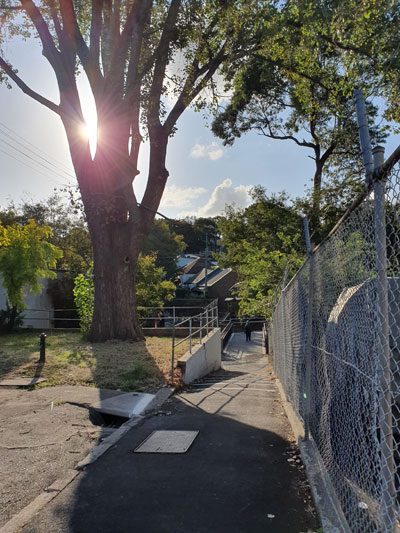

We walk down the hill to a newly-built footbridge over the canal. On the other side of the dip the street climbs up between the Federation houses of re-gentrified Annandale.

Everything here looks new, but the two playgrounds are roped off to prevent children from disobeying social distancing rules. This tiny canalside reserve is called ‘Douglas Grant Memorial Park’ in honour of an Aboriginal man whose original name was Ng:tja. The survivor of a massacre, in 1887 he was taken as a toddler from his North Queensland home thousands of kilometres away and brought up in Annandale as a member of his captor’s family. His story is told on two plaques. It does not end well.

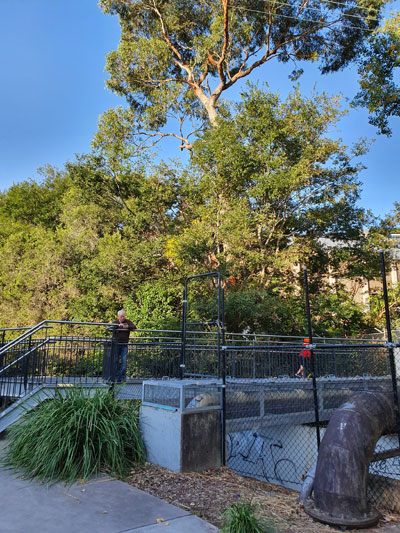

By taking a short walk along where this narrow park skirts a series of backyard fences, I can look across to the place where I had earlier tried bush-bashing. The clear band of water that I couldn’t see from the other side reflects the sky, but the graffiti is old and dilapidated, as if the renovation of the area has made the canal too public for spray painters.

This nook in Annandale is a revelation to me. But not to locals of course. Not the cyclists and joggers intermittently crossing the bridge. The two young men casually shooting a basketball. The squealing children doing wheelies on their scooters. Nor the three teenagers sitting at a picnic table and idly chatting not quite 1.5 metres apart.