It is a warm Sunday afternoon in October, and we are on the forecourt of Old Parliament House – now called the Museum of Australian Democracy. The air is thick with fluffy seeds from Canberra’s avenues of exotic trees. In some places they lie in the gutters like drifts of snow. But despite the pleasant weather there is that sense of manicured desolation here that sightseers from other cities find remarkable about the national capital.

Perhaps it is not fair to judge the scarcity of people on this particular day. Potential visitors to museums have probably all been sucked away to the other side of Lake Burley Griffin where Floriade, the annual spring festival, is in full bloom. Â We have chosen to avoid the flower beds and ferris wheels and instead are standing on the best example of pavement graffiti in the Australian Capital Territory.

The controversial Aboriginal Tent Embassy was originally established on the lawns of Old Parliament House in 1972, claiming to represent the political rights of Australian Aboriginal people. After being removed several times it has now been in place since 1992. There is an official Aboriginal Tent Embassy website, and you can also read a potted history on Wikipedia.

Today the tents and decorated sheds appear to be empty and all that there is to see are signs and flags, piles of firewood and a smear of smoke from the smouldering sacred fire. And of course, the decorated forecourt. Around its edges there are recently painted slogans and symbols, but mostly this expanse of paving is crowded with a worn menagerie of animals and plants painted in imitation of various styles of Aboriginal rock-art.

In their book Inscribed landscapes archaeologists Bruno David and Meredith Wilson draw parallels between Indigenous rock markings and graffiti. What better place than here at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy to reflect on their contention that all inscription, including modern graffiti and contact-period rock-art, is about the politics of turf. Inscriptions, they maintain, colonize space.

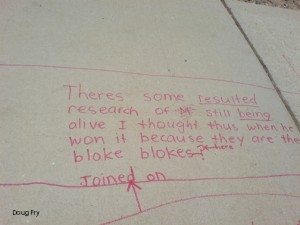

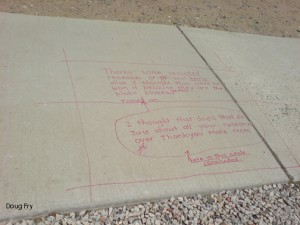

Apart from a failed first year university class (and my weekly trash TV fix of Bones) I don’t really have any experience in the field of psychology, so I’m only making a vaguely educated guess when I say that the author/illustrator of this work is probably a paranoid schizophrenic.

Apart from a failed first year university class (and my weekly trash TV fix of Bones) I don’t really have any experience in the field of psychology, so I’m only making a vaguely educated guess when I say that the author/illustrator of this work is probably a paranoid schizophrenic.