Writing graffiti can be a way of claiming or re-claiming territory. That is what has happened at the former Parramatta Girls Home, as I found when I visited the site this week. I did not go with the intention of photographing pavement graffiti, but I unexpectedly came across the letters ILWA and the silhouettes of children sprayed on footpaths and concrete verandahs there.

The former girls’ home is part of the Parramatta Female Factory Precinct whose history of incarceration and ‘care’ of women and children extends from 1821 to 2008. Numbers of inmates at the Parramatta Girls Home peaked in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, as courts committed hundreds of girls every year to spend months or years in the facility.

Sent to this institution at the age of 15 for being ‘in moral danger’, Bonney Djuric is now an artist, activist and historian. In 2006 she founded the support group Parragirls and was inundated by responses from women still living with memories of the physical, sexual and psychological abuse they suffered there. Now the Director of the Parramatta Female Factory Memory Project, Bonney has been instrumental in the campaign to preserve and dedicate the Parramatta Girls Home and the adjacent Female Factory as a Living Memorial to the Forgotten Australians and others who have been marginalised by society.

One of the buildings, renamed Kamballa in the 1970s, is now the centre of the Parramatta Female Factory Precinct Memory Project, and it was Bonney who sprayed the ghostly silhouettes on the concrete in 2013 as a way of reasserting the presence of those forgotten children who passed through the institutions on this site.

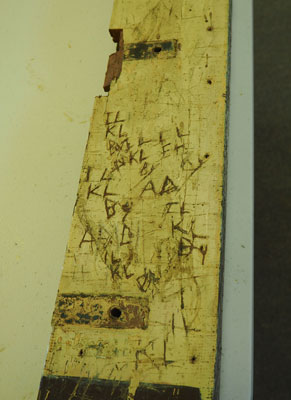

More puzzling is the symbol ILWA, also sprayed by Bonney at the same time. It mimics graffiti scratched into the woodwork at the Parramatta Girls Home, she tells me, and stands for ‘I Love Worship and Adore’. Bonney showed me examples of the original graffiti, some of it dating to the 1940s, on doors that have been preserved. Not only a message of affection, it also represented solidarity and resilience amongst the girls. It was a way of asserting ‘I am here’.

In a blog post several years ago I wrote that all inscription is about the politics of turf. Back in the days of the Parramatta Girls Home, the girls who scraped their messages into the woodwork would have understood that theirs were assertive acts of defiance, but they could not possibly have imagined that years later their marks would be regarded as significant documents that offer an interpretation of the site that is as important as official archival material. Nor would they have imagined that their marks would be deliberately copied as a way of reclaiming territory on their behalf.