There are still people in Sydney who pine for the line painted down the centre of city footpaths to separate pedestrians moving in opposite directions.

Much has been written about the historical battle between pedestrians and motorists when the car took over from horse-drawn vehicles and commandeered the road. And in contemporary times, with the resurgence of bicycle riding, much is being written about the battles between cyclists and motorists on the road, and between cyclists and pedestrians on the footpaths.

But I have been interested for a while in the civil war amongst walking citizens, and the boundary lines that have, from time to time, been drawn up in an attempt to keep the peace. Turning up photographs of these lines has been difficult but, in a current museum exhibition I found what I have been looking for.

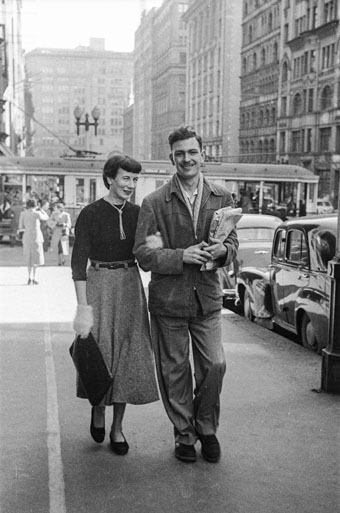

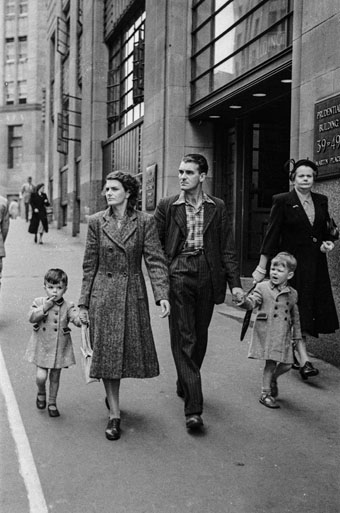

Street photography at the Museum of Sydney displays photographs taken by the men who, from the Depression 1930s to the Post-war 1960s, used to stand in licensed positions and take snaps of city footpath walkers then press upon them a ticket with the address of a nearby studio where they could purchase same-day prints.

For people who bought them it was perhaps the best photo they had of themselves, the best photo their families had to remember them by. But the exhibition’s curators also invite visitors to see what else they can find beside the main subjects of the photos – items of clothing or accessories that date the pictures, figures in the background, still-recognisable locations in Sydney. I looked for and found the centre lines.

A by-law requiring foot passengers to ‘keep to the right’ on footways existed in Sydney from around 1900 but it was largely ignored. In a letter to the Mayor in 1902 a Mr George Richards fumed that ‘the people walking in our city are like a lot of cattle that has got into a barn and wander about looking for a place to get out. Surely you can do something to prevent this sort of thing’.

The City of Sydney Archives and clippings books reveal that Mr Richards was not the only one infuriated by the unruly users of Sydney’s footpaths. One columnist in 1911, for example, complained about there being ‘no visible admonition to keep to the right’.

Somewhere along the way the rule changed to ‘keep to the left’ so that pedestrians did not have their backs to the traffic if they stepped off the footpath onto the roadway. By the mid-1920s authorities in Melbourne had not only copied this rule but had painted white centre lines.

But it was not until 1948, after two years of to-ing and fro-ing between Sydney City Council, the Police Department and the Department of Motor Transport, that Sydney had a trial of centre lines on parts of George, Market, Pitt and King Streets, along with the stencil ‘KEEP LEFT’ at appropriate locations.

The trial was a success and the area of the city with lines down the middle of footpaths was extended. They were regularly repainted by the Department of Motor Transport but the KEEP LEFT stencils were not maintained because they were considered to be of little value.

In 1961 the Council wanted to extend

the scheme further from Sydney Central to Haymarket and Railway Square, but the

Department of Motor Transport had had enough, thanks to restricted finance and

a heavy volume of work. The existing lines, which by then were painted yellow,

were allowed to wear away.

They were not re-introduced and, in justification, the City Planner pointed out that ‘pedestrian traffic by its nature is unpredictable and it is not considered feasible that pedestrians can be controlled in the same way as vehicular traffic, nor is it considered desirable that they should be’.

Nevertheless, in the following years a steady stream of letter-writers pleaded for the return of the centre line. Mr Byott of Belfield’s 1974 letter was typical: ‘After suffering another Christmas shopper’s charge on the footpaths in the City its about time something was done about it. Please bring back the “YELLOW LINE” that adorned Sydney City footpaths a decade ago, so at least the poor employees in the city area (like myself) get a bit of a “fair go” at all times’.

Council toyed with the idea of reintroducing the centre lines but, apart perhaps from a period in the 1980s (something I’ve been unable to confirm) they never have.

However newspaper letter writers like Ms Alicia Dawson of Balmain have not forgotten. In 2015 she complained about the ‘very frustrating pace of stop/sidestep/duck and weave’ on city streets and cried, ‘Bring back the white line up the middle of the footpath or otherwise I might well be driven to march around the city carrying a large hot dog smothered in tomato sauce on a stick while yelling “keep left, keep left” at the top of my voice.

In 2017 Ms Dawson was still harping on the subject and others agreed, urging the City of Sydney to ‘reinstate the system of the 1940s and 50s, when Sydney footpaths had a painted line down the centre’. Yet others were incredulous: ‘Are you serious? What a waste of time and money to paint lines down the centre of footpaths. Will we have to use hand signals if we wish to overtake?’

Ms Dawson may consider that ‘other people’ on city streets lack manners, but letter writers and columnists who hold similar sentiments are not particularly polite themselves. Mobile phone zombies, they growl about fellow footpath users. Self-absorbed texters. Oblivious to the swirling tide around them. Cursing into mobile phones. Smombies. Large contingents of residents walking shoulder to shoulder. A phone-twiddling human wall. Dopey dawdlers. The swayer describing a zigzag path. All over the place. Crisscrossing. A free-for-all. Dawdling tourists. Heel steppers. Sudden stops and turns. Slowcoaches. Slow old people with huge, boxy Volvo bums. Running groups and other pavement irritants. Window shoppers. People who bash into others with a backpack. Gophers that nearly run you over. And the worst pavement tyrants, those mothers with bigger-than- Texas prams.

So the indignation, the jostling and the sledging continue, and the keep-left rule is all but forgotten. There are some who still believe that the thin yellow line would have a calming effect but probably, as the City Engineer said back in 1974, the reintroduction of marked centrelines on footways would be of doubtful value.

Images

The photographs were all taken by a street photographer in Martin Place, Sydney, between May and December 1950. The have been reproduced courtesy of the Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums.

References:

Brown-May, Andrew, ‘The highway of civilisation and common sense’, Urban Research Program Working Paper No.49, ANU, 1995.

City of Sydney Archives 1902/0068 (1902); 268/60 (1960-1978); CRS 1083/14/70 (2011)

Sydney Morning Herald letters to the editor and columnists 2003-2017 (details available)

![Road safety poster using Ian Macmillan’s famous 1969 photograph, issued by the Kolkata [Calcutta] Traffic Police in February 2013.](http://www.meganix.net/pavement/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/BeatlesKolkata_65951375_9358d13f-8536-4294-98c6-2b358c560b1f.jpg)